Company Breakdown: Airbus SE (AIR)

As I continue exploring companies and industries, I had the opportunity to construct a report on Airbus SE, the European aircraft manufacturer sharing a duopoly with Boeing.

I‘ve never researched the aerospace industry, mostly because I heard it was a very complex market where extracting value is incredibly challenging. Still, knowledge compounds, and exploring new industries never hurts.

Full disclosure: I didn’t invest in Airbus as I deem it overvalued, as you will see. However, I still hope that someone reading this will find the insights shown useful, if not for investing, at least for general knowledge.

Introduction

The company found its roots in 1969 after major European aerospace companies decided to form a consortium to compete with the U.S. giants. Airbus became part of a duopoly with Boeing in the late 1990s, following waves of industry consolidation.

Company Overview

Airbus’ business is cyclical, experiencing big swings in performance.

The company is divided into three segments: Commercial Aircraft, Defence and Space, and Helicopters. Its revenues originate globally, as shown below:

Commercial Aircraft

Commercial aerospace is one of the most complex industries in the world. To make a single plane, thousands of companies across the supply chain are involved in a process that takes years to complete.

Boeing and Airbus share a duopoly in the Aircraft segment, where parts get assembled into the final plane, which is then sold to airlines.

Every link in the supply chain struggles to create economic profit (measured as the spread between ROIC and WACC), given high capital intensity, stringent standards, limited pricing power, and volatile demand.

For clarity, the landscape was similar 10 years ago, with airlines, airports, and manufacturers facing challenges in creating a positive ROIC-WACC spread.

After the pandemic years of over-supply, aeroplanes are now under-supplied, with record order book levels and supply chain bottlenecks.

Defence and Space

Airbus’s strategic importance to European governments arises not only from the need for a domestic fleet but also from the company’s role in developing defence and space-related products. This segment is further divided into three divisions: Air Power, Space Systems, and Connected Intelligence.

The Air Power division designs, develops, delivers, and supports military aircraft. The market is dominated by large and medium-sized American and European companies and requires extensive knowledge of basic airframe models.

The Space Sytems division serves both commercial and military customers. It offers satellite solutions for telecommunications, Earth observation, and navigation, and manufactures orbital and space exploration systems. The commercial business is highly competitive, while the military business shows characteristics similar to the Air Power division.

Finally, the Connected Intelligence division provides products and services for space and terrestrial connectivity, data management and intelligence, military multi-domain operations, and cyber security.

Helicopters

The Helicopter segment is highly innovative, as the company explores projects like the eVTOL (electrical vertical take-off and landing) aircraft and advanced military helicopters.

Airbus is a leader in the Civil & Parapublic (C&P) market, with a 48% market share, while Boeing dominates the military sector with a 38% market share, compared to 16% of Airbus. Over the next 10 years, Airbus expects deliveries of 6,900 C&P and 6,800 military helicopters.

Furthermore, 47% of sales in the segment derive from services such as maintenance and repair, contributing to better margins.

Strategic Overview

Unit Economics

Revenues are recognised at the delivery of the goods and services or when a major milestone is reached in the agreement. However, the company registers a significant amount of pre-payments. In particular, in the Commercial segment, the client pays roughly a third of the aircraft price when the order is placed, financing part of the working capital needs. This is reflected in the firm’s balance sheet, where enormous amounts of deferred revenues skew the net working capital (NWC) towards structurally negative territory, significantly lowering the proprietary capital employed. The cost of sales is by far the biggest expense, accounting for roughly 85% of revenues in 2023. Operating costs, mainly SG&A and R&D, further lower profits, resulting in a reported EBIT margin of 7% in 2023. Because Airbus can finance its operations through its working capital, the company has little leverage, with a net D/E ratio of about 5%. Finally, the effective tax rate was 24.24% in 2023 (and averaged 23.8% in the past 10 years), resulting in a profit margin of 5.79%.

In summary, given the big impact of COGS, Airbus is a structurally low-margin business with significant volatility.

The company provides an adjusted EBIT measure, but after reviewing the adjustments over the past 10 years, I chose to treat some of them as operating due to their recurring nature. Additionally, given the long-term benefits of R&D projects, I decided to capitalise R&D expenses.

Industry Dynamics

Commercial Segment

In the Commercial segment, Airbus has operated in a duopoly with Boeing since the 1990s, competing in a market with a highly concentrated customer base. Airlines typically commit to purchasing multiple planes, so losing a customer has significant repercussions. This concentration of buyers grants airlines modest pricing power. Indeed, offering a 40-60% discount on list prices is common practice.

Cost efficiency is vital for airline profitability, making them highly price-sensitive and pushing Airbus and Boeing to focus on cost innovation over performance differentiation. Airlines themselves offer a commoditised service to passengers, with ticket prices frequently being the main factor in customer decisions. This focus on costs transfers to Airbus and Boeing, who face constant pressure to keep prices low.

Competition between the two companies is intense, often leading to price wars to protect market share. However, there are structural limits to price competition: as one company gains market share, its backlog grows, lengthening delivery times. At a certain point, airlines may prefer paying a bit more for a shorter waiting time, helping to stabilise market share in the industry.

On the supply side, Airbus sources parts from thousands of OEMs. Yet, key components like engines and landing gears come from a few specialised suppliers with substantial bargaining power, especially with the current shortages. Overall, operating in this industry is complex, with unattractive unit economics and pressures from both suppliers and customers. The Commercial segment averaged 5.1% EBIT margin in the past 10 years.

Defence and Space

The Defence and Space segment is likely the most challenging area for Airbus. Similar to the Commercial segment, it features a few specialised suppliers, a concentrated customer base, and tough competition. However, given that the primary customers are governments, buyers have even more bargaining power, and competition is more intense.

To secure government contracts, companies must go through competitive bidding processes, which intensifies rivalry. Given the sensitivity of these projects, governments also tend to spread their risk by working with multiple suppliers, making it nearly impossible for any single player to dominate.

Unlike the Commercial segment, Defence and Space projects offer more opportunities for differentiation, as customers seek not only cost efficiency but also cutting-edge innovation and performance. However, this demand for innovation only adds pressure on Airbus, as the company is unlikely to secure a leading position even with the best products. The company faces competition from pure-play Defence firms like Lockheed Martin, which have more resources to use in this highly innovation-driven field.

Despite the high barriers to entry, including stringent regulations, advanced R&D requirements, and substantial capital needs, the Defence and Space segment has generally struggled to be profitable. Over the past decade, it has averaged an EBIT margin of -9.15%, underscoring the complexity and difficulty of operating in this industry.

Helicopters

Turning to the Helicopter industry, the segment brings together all the dynamics mentioned above, as Airbus holds a major presence in both military and C&P markets. Despite these challenges, the Helicopter segment is the most profitable, with an average operating margin of 6.76% over the past decade. This profitability is largely driven by after-sales services, which make up 47% of the division’s revenue.

The Moat

Airbus's primary competitive advantage lies in the significant entry barriers of the aerospace industry. Manufacturing aircraft demands substantial resources, both in terms of time and capital. Economies of scale are essential for maintaining Airbus's profitability, and due to the industry's unattractive unit economics, few companies would be willing to take such high risks for minimal rewards.

Barriers to entry extend beyond just financial resources. The manufacturing process is incredibly complex: a new entrant would need to establish relationships with thousands of stakeholders across the supply chain and develop a robust infrastructure to manage these interactions. Even if a company were to succeed in this endeavour, it would still need to design a superior aircraft, where heavy regulations restricting innovation add another layer of difficulty. Moreover, even if a new player were to create a better aircraft, this does not guarantee success. The industry is governed by established standards throughout the value chain, and purchasing an aircraft typically entails a 30-year commitment. This long-term agreement creates a strong preference for stability, leading companies to resist change in favour of proven processes and reliable performance. Finally, the strategic nature of operations leads to the need for government support, further complicating entry from new competitors. Furthermore, the long duration of projects contributes to high switching costs: once an order is placed, withdrawing becomes costly and complicated.

These factors prevent players from entering but do little to help the company achieve extraordinary results. The industry dynamics outweigh Airbus’ competitive advantages and lead to rather low ROIC levels.

Value drivers

How can Airbus outperform Boeing, given that both companies share similar competitive advantages?

To provide a comprehensive answer, let's break down ROIC into its two key components: the NOPAT margin and the invested capital turnover (ICT). The NOPAT margin, calculated as NOPAT/revenues, reflects a company's profitability and is typically influenced by the differentiation of its products. In contrast, ICT, measured as revenues/invested capital, assesses a company's efficiency in generating revenue and is linked to cost leadership and operational effectiveness.

Industry dynamics reveal that both companies have limited leverage over margins, and their NOPAT margin is primarily affected by market cyclicality. However, Airbus can gain an advantage by enhancing its ICT, and it is already doing so. For example, Airbus operates with less financial leverage than Boeing, as it primarily finances its operations through working capital. This means that customer pre-payments effectively reduce the amount of capital Airbus needs to deploy, improving ROIC. That said, scaling this business has limits: as project durations continue to increase, customers may eventually turn to competitors, establishing a structural ceiling for ICT.

Ultimately, I believe Airbus can gain a competitive edge by prioritising efficiency and production volume over pricing power. To succeed, Airbus must deliver the most cost-efficient aircraft in the shortest timeframe, all while minimising errors.

As noted earlier, ROIC levels are not particularly high, averaging around 10.34% after capitalising R&D expenses. Does this imply that Airbus is a poor investment? Not necessarily. Investors should focus on marginal ROIC and the price they pay for that return.

Risks

China

There is one exception that is likely to overcome all the high entry barriers of the industry: COMAC. The Chinese state-owned enterprise received EUR 50bn financing to develop a domestic fleet. The C919, in direct competition with the A320, has already received authorization to fly in China, and will likely keep gaining domestic market share. Additionally, as most of the parts are produced in the EU and US, and are the same used by Airbus and Boeing, COMAC expects to obtain the EASA certification by 2025, opening the doors to Europe and several emerging markets. Given geopolitical tensions between China and the US, the certification in North America will likely take more time. Even though I believe COMAC will be a threat from the 2030s, given that most of the backlog is secured until then, its entrance into the market could pressure the already stressed supply chain, hurting Airbus’ margins and efficiency.

Environmental pressures

The rise of pressures to reduce emissions forces Airbus to keep innovating. New aircraft must be ever more efficient in their fuel usage, but as we reach the limits of technology, incremental improvements take more time and capital.

Government role

Having the government as a client and as a shareholder is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the risk of bankruptcy is almost non-existent as the government is likely to subsidise or save the business in times of crisis. On the other hand, the same government that saves you might limit strategic flexibility, forcing Airbus to produce domestically instead of outsourcing to cheaper locations. Moreover, by being tied to the government, the company is at least indirectly exposed to geopolitical risk, threatening its global client relationships.

Cyclicality

Last but not least, this is a cyclical business. Air travel demand, raw material costs, and supply chain volatility depend on systemic factors, and Airbus must be exceptional in navigating swings in demand and supply disruptions.

Valuation: The Narrative

Every valuation is about translating a narrative into numbers.

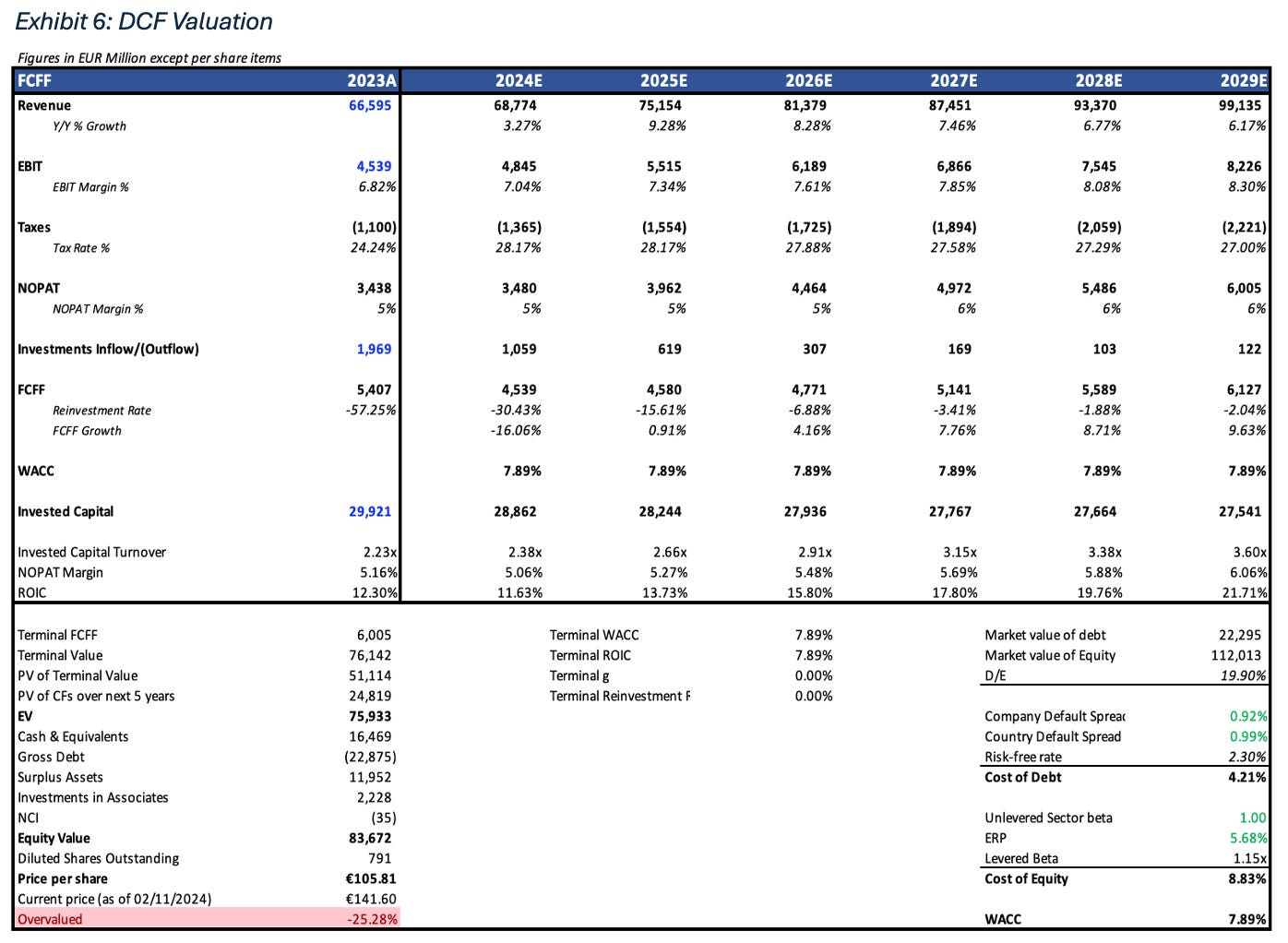

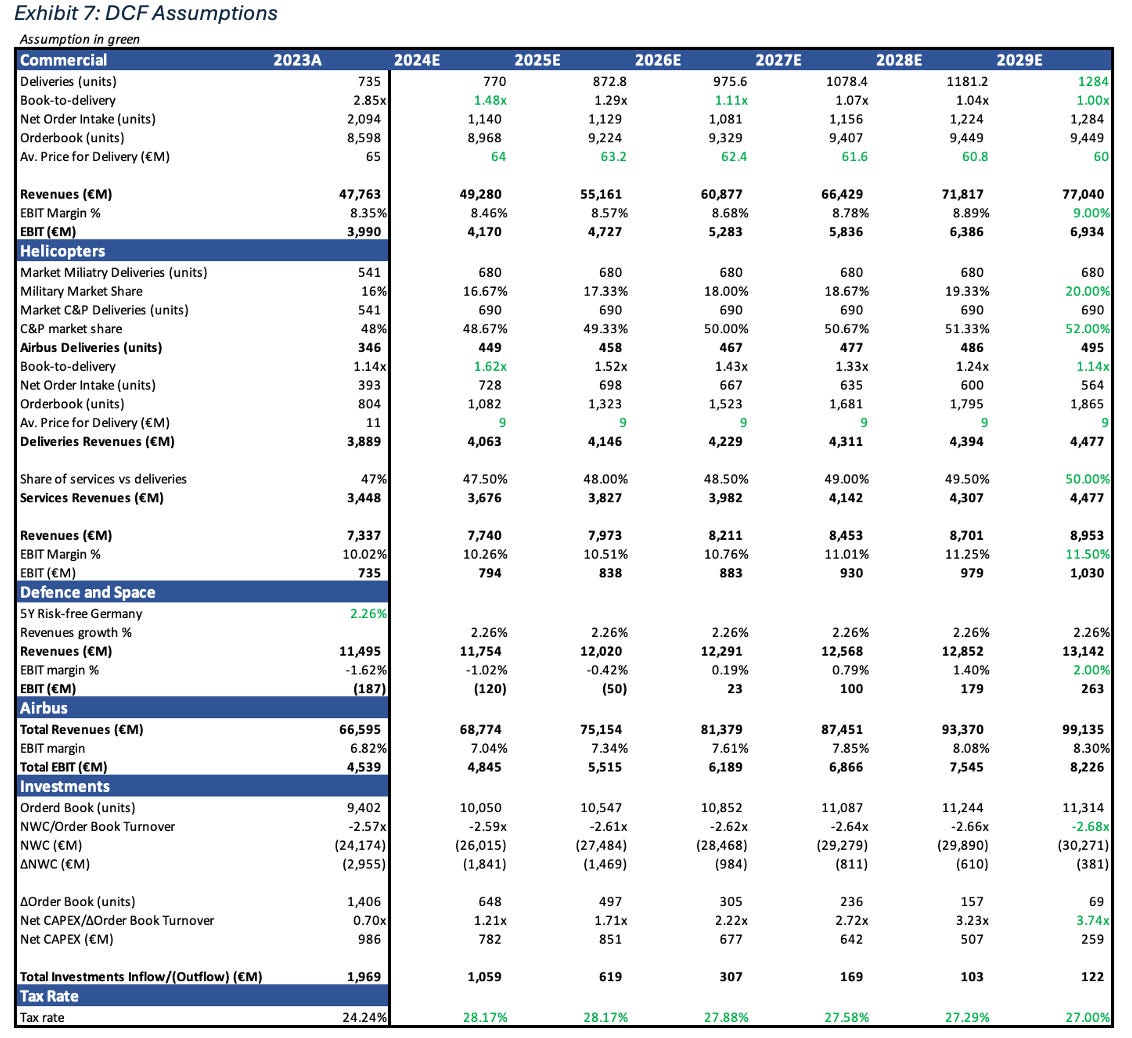

Given Airbus's structure, cyclicality, and uncertainty, I decided to forecast each segment independently for five years before assuming stable growth.

Here’s my 2 cents on Airbus’ future: over the next five years, the Commercial segment is poised to benefit from strong, secured demand and Boeing’s recent challenges. While margins will see slight improvements, the entry of COMAC will exert pressure on key suppliers and pricing. The helicopter segment is expected to grow as Airbus captures market share in both commercial and military sectors. Additionally, as services increasingly contribute to revenues, margins are likely to improve. The Defence and Space segment will experience gains from heightened government spending on military projects and is projected to become profitable by 2026. To support growth, Airbus will need to invest significantly in production capacity, with much of this capital financed through net working capital, reducing capital employed and enhancing ROIC. Following a recent proposal in France, taxes will rise over the next two years before aligning with the core business tax rate. Finally, COMAC will represent a significant threat in the next decade. As a result, I believe that Airbus will maintain a ROIC = WACC in perpetuity.

Next, I will discuss the primary drivers of my model, with a full summary of the assumptions available in Exhibit 6 of the Appendix.

The Commercial segment’s performance depends on aircraft deliveries. While management aims for a monthly production rate of 75 A320s by 2027, I anticipate Airbus will reach this target by 2029 due to supply chain pressures from COMAC. Including other aircraft families, Airbus is projected to achieve 107 deliveries per month by 2029. Simultaneously, as Boeing attempts to reclaim market share by lowering prices, the average delivery price is expected to drop from €65 million to €60 million. Overall, segment revenues will grow at a CAGR of 9.35%, with operating margins improving from 8.35% to 9%.

The Helicopter segment is forecasted to experience stable growth in both commercial and military markets. Following new military programs in collaboration with NATO and Boeing’s reduced credibility, Airbus is expected to increase its market share from 48% to 52% in the commercial market and from 16% to 20% in the military sector. Furthermore, as services grow to constitute 50% of the segment’s revenues by 2029, the EBIT margin is projected to rise from 10% to 11.5%, with revenues expanding at a CAGR of 2.96%.

The Defence and Space segment is anticipated to grow in line with economic trends. To estimate top-line growth, I used the yield of the 5Y German Bund, which serves as a suitable proxy for nominal GDP growth in euros. I expect the segment to achieve profitability in 2026, with an EBIT margin of 2% by 2029.

Investments, defined as ΔNWC + CAPEX – D&A, are primarily driven by the order book. As Airbus's order book expands, NWC decreases significantly due to customer pre-payments. Concurrently, to meet rising demand, Airbus must scale up production. I expect orders to increase at a slower pace, with book-to-delivery ratios declining from 1.48 in 2024 to 1 in 2029 for the Commercial segment and from 1.62 to 1.14 in the Helicopter segment. The NWC/order book turnover (NWC/Order Book) is projected to decrease to -2.68, highlighting the NWC's ability to finance Airbus's operations, while the net CAPEX/ΔOrder Book turnover will stabilise at the post-pandemic average of 3.74. These measures were selected as they correlate with investments’ economic driver: the order book. Indeed, they showed lower volatility across economic cycles, better tracking expansionary and contracting investment needs.

The FCFF is expected to grow at a 6.2% CAGR between 2024 and 2029.

For most target ratios, I utilised historical averages, focusing on expansionary periods where necessary to reflect conditions likely to occur over the next five years.

ROIC is projected to increase from 12.3% to nearly 22%. While this may appear optimistic, high marginal ROICs are characteristic of expansionary and under-supplied cycles. For instance, Airbus’s ROIC surged from 9.7% in 2015 to 16.45% in 2019, during a similarly under-supplied cycle with robust demand.

As previously mentioned, COMAC will pose a significant threat in the 2030s. Over the past decade, Airbus’s average ROIC has been around 10%, suggesting that with the entry of a third competitor, the company’s ROIC could align with its WACC.

Finally, here are the key components of the WACC: since the valuation is conducted in euros, I used the 10Y German Bund as the risk-free rate. The cost of debt is 4.21%, which includes the country-default spread (adjusted for geographical revenue distribution) and the company-specific default spread. Given that the benchmark is the MSCI ACWI, I derived the cost of equity at 8.83% based on the implied expected return on the index, adjusted for geographical revenue exposure. Therefore, the WACC is calculated at 7.89%.

The valuation results in a target price of €105.81, roughly a 25% downside from the current price of €141.60. A visual summary of the valuation can be found below:

Conclusion

In conclusion, while Airbus possesses a strong moat and is likely to generate impressive marginal ROIC, these factors are already more than priced in by the market. Ultimately, investing is about getting value for a fair price. At this level, I do not anticipate that the company will outperform the MSCI ACWI or provide a sufficient margin of safety to mitigate uncertainty. Therefore, I reiterate my recommendation to NOT BUY.

I welcome any feedback and input on the research. After all, I only dipped my toe in the industry, and I’m sure there are people with far more experience than myself who can provide more in-depth insights.

Thanks for your time.