Earlier this year, during a mentorship program, I encountered Judges Scientific, a holding company consolidating the scientific instruments industry since 2005. Exactly one year ago, the company was one of the rare 100-baggers listed on the LSE, with the stock price compounding at an astonishing 28% CAGR over 18 years. Fast forward one year, and the price has halved, offering what I believe is an attractive investment opportunity. Hence, I decided to dig deeper. My mentor always says that if you really want to learn something, you either have to write about it or teach it to someone. Since all my friends and family are wise enough to avoid sitting through a never-ending tedious spiel about a company they've never even heard of, I figured an article would be the safer choice, and here we are.

The Business Model

As a buy-and-build, Judges Scientific has a pretty straightforward business model: the firm identifies, acquires, and improves companies in the scientific instruments industry. In essence, the firm’s strategy resembles that of private equity, benefiting from deleveraging, multiple expansion, and operational improvements, with one key difference: Judges does not acquire companies to eventually resell them, but instead intends to hold and grow them over the long term.

Since its inception in May 2005, the company has successfully acquired 25 companies for an average multiple of 5x EBIT and a range between 3x and 7x. The company also uses leverage up to 3x EBITDA, and the usual transaction value ranges from £6M to £12M.

An important aspect of Judges’ model is the company’s hands-off and decentralised approach with its subsidiaries. Once acquired, targets retain their independence and culture, and this makes prospective sellers particularly comfortable in joining Judges. However, as a result, the buying process is far more important than the building one, since most of the returns derive from correct capital allocation decisions rather than improvements in the targets. At the same time, Judges provides access to better financing as well as foster best practices to strengthen governance and financial control. In other words, Judges acts as a supportive and non-invasive parent.

Capital allocation decisions are made at a holding level, allowing for optimal decisions based on the best expected returns available across the portfolio. Broadly speaking, Judges follows a philosophy similar to that of Berkshire Hathaway, for those familiar with the firm.

Unit Economics

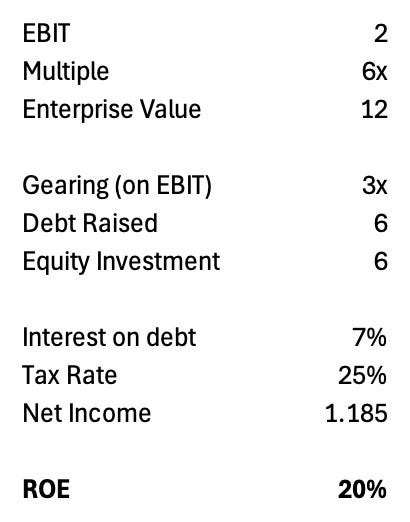

To better illustrate how Judges generates returns, I will go through a numerical example:

Assume the target company generates £2M in EBIT, and we are able to buy it at 6 times, for a total enterprise value of £12M. Thanks to our good reputation, we are also able to raise 3x EBIT in debt. As a result, we will need to invest only £6M out of our own pockets, and finance the rest through debt. Finally, to get to what we shareholders will own, we need to deduct interest from the debt raised and taxes. This results in a net income of ~£1.2M, for a return on equity of ~20%. Moreover, Judges usually repays the debt used for the acquisition in 3 years. This means that after 3 years, in addition to our 20% return coming from the income generated by the target, we will own 100% of the company. Therefore, our initial investment of £6M is now worth £12M, and returns us a constant 20% annually.

Now this “trick” works only if two conditions hold: the company we buy doesn’t decrease in value, and we are able to repay the debt used for the acquisitions. While the private equity industry struggles to make this happen at attractive returns, I will show in the next section why Judges is so good at consistently employing this mechanism.

Investment Case

Now that it is clearer why this model works from a numerical perspective, let’s try to better understand the qualitative side of things. In other words, why doesn’t every company just go on a buy-and-build spree to generate returns similar to Judges?

Well, a couple of things make this company particularly appealing…

First, the industry in which Judges operates, i.e. scientific instruments, has strong tailwinds, favouring organic growth on top of the returns generated from the acquisitions. While I will deep dive into the industry analysis in the next section, it is worth mentioning that increased R&D spending, progress in higher education, and rising need for measurements and testing allowed the company to generate a 7% CAGR organic growth since 2005. Picking the right companies is difficult enough on its own, so doing it in a market with strong secular tailwinds simply reduces complexity and risk.

Second, the companies targeted by Judges exhibit a very strong competitive position. They often operate in tiny, global niche markets, where they are leaders, if not monopolists. As a result, these firms can maintain high, healthy margins (mid to high-teens operating margins) while needing little reinvestment to maintain their competitive position, allowing for strong cash flow generation.

Third, as scale increases, Judges benefits from diversification at a holding level. If you’re thinking that buying one of these companies on its own is risky, well, you’re right. This is because usually, these firms offer highly specialised, profitable big-ticket products and services, with few yearly orders and recurring revenues. Therefore, even though in the long run demand is somewhat stable given the industry’s tailwinds, individual companies might experience short-run fluctuations. However, if each acquisition becomes part of a wider portfolio, where each niche is relatively uncorrelated from the other, the problem fades away. As a result, given that debt and capital allocation are managed at a holding level, Judges will virtually always be able to pay its debt obligations and generate strong cash flow.

To better illustrate Judges’ diversification, I attach a slide from the FY2024 presentation.

Note that most of the manufacturing happens in the UK, denominated in £.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the management has consistently shown superior capital allocation skills and discipline in acquisitions. CEO and founder David Cicurel has a crystal clear understanding of what he looks for, and is willing to go years without acquiring a company if he thinks that no target is up to standard. While this might seem superfluous to some, the impact on shareholders is enormous, and finding a management that truly understands capital allocation and incremental returns is terribly difficult. Ultimately, how much you pay is as important as what you buy, an aspect that, unfortunately, most managers seem to forget or choose to ignore.

The Industry

To have some visibility over Judges’ future, we must understand how the organic and inorganic aspects of the business model function and what their drivers are.

Inorganic view

For the business model to be successful, the company must be able to continue making acquisitions at attractive terms. To determine whether this is feasible, we must answer two questions: how big is the pool of targets, and can other competitors threaten Judges’ pipeline of deals?

In response to the first question, the pool is still very large. The firm has made 25 acquisitions to date, and it states that the UK alone has more than 2,000 privately held companies operating in the scientific instruments industry. Additionally, Judges recently started conducting cross-border acquisitions, as shown by the purchase of Luciol Instruments, based in Switzerland. Finally, with growing size, the firm can also target bigger companies, such as Geotek, acquired for a total compensation of ~80m in 2022. As a result, I don’t expect the company to run out of targets anytime soon.

Regarding competition, Judges is not the only company adopting a buy-and-build model in the scientific instruments industry. In particular, Halma plc (HLMA) and SDI Group (SDI) share similar structures and have a strong presence in the UK market. However, Halma, because of its substantially larger scale and focus on specific sub-verticals, might compete with Judges only occasionally. Indeed, Halma’s average acquisition value ranges from £20m to £40m, and the firm only targets companies in the safety, environmental & analysis, and healthcare sectors. Moreover, Halma tends to acquire businesses that differ from Judges’ model, frequently generating a substantial share of revenue through services. In contrast, SDI Group is a direct competitor, though considerably smaller (generating approximately half of Judges’ revenues). Yet, SDI is facing a turbulent period after long-standing CEO Mike Creedon stepped down unexpectedly in January 2024, leaving doubts on whether the firm will be able to continue its strategy effectively. Furthermore, when it comes to dealing with small-medium-sized businesses, reputation, track record, and trustworthiness are at least as important as the price offered, and Judges outcompetes SDI in these aspects, especially after the latter’s management change. Lastly, private equity firms are not in direct competition with Judges, given the small size of the targets, but this could change as the firm grows.

In summary, while some competition exists, especially if Judges decides to target bigger companies, the vastness of the deal pool and Judges’ strong positioning suggest the company will be able to successfully execute its strategy in the foreseeable future.

Organic view

As mentioned, Judges operates in the scientific instruments industry. This can mean everything and nothing, so let’s try to be more specific. Judges’ portfolio of companies can be split into two segments: Material Sciences and Vacuum. Each contributes roughly half of the group’s revenue, with Material Sciences accounting for a slightly larger share. Material Sciences is concerned with studying, testing, and analysing the properties and behaviours of materials, while Vacuum products are essential for creating and maintaining controlled vacuum environments required for scientific experiments, manufacturing processes, and advanced research. Both segments produce instruments intended for different end uses, including industrial, life sciences, environmental, and semiconductor applications.

Since its inception in 2005, Judges has benefited from very strong organic growth (~7% CAGR on revenues). To better understand what the future might look like, I will try to make sense of these results.

During the 2025 AGM, Judges estimated that ~50% of revenues are generated from universities, ~33% from corporations, and the remaining ~17% from global testing firms. Some of Judges’ subsidiaries start by selling only to academia, and then move into the commercial space. Yet, clearly, academic research has been a fundamental driver of growth for Judges, with global R&D spending on higher education tripling over the past 20 years. Additionally, as corporations increased their R&D investments, Judges has been able to capture part of that growth, directly selling to several OEMs. Finally, another important source of growth has been the Chinese market, which in the last 7 years went from being irrelevant to representing about 10% of the company’s revenues. Here, Judges has been selling mostly to academic institutions, which benefited from vast investment programs by the government. However, as China shifts resources to stimulate domestic consumption, Judges will likely experience increased competition, particularly in selling to corporations. Indeed, while academic research often requires the best possible scientific instruments, Chinese corporations are more prone to buy cheaper machinery, often produced domestically. Coupled with a lower GDP growth, this is likely to result in more normalised growth rates in the region.

The exceptional organic growth experience by Judges in the past 20 years is linked to secular trends characterising the scientific instruments industry. To summarise:

Rising Global R&D Spending: As already mentioned, higher R&D intensity has been a strong driver for Judges, as most of its subsidiaries supply high-precision instruments used in research projects globally.

Increasing Awareness and Regulation on Sustainability: Many of Judges’ subsidiaries are directly involved in ESG-related projects, including research on climate change, exploratory analysis for infrastructure construction, and testing for clean energy solutions.

Ageing Population and Healthcare Research: As a significant portion of Judges’ revenues comes from life sciences, increased spending for healthcare research has been a strong driver of performance.

Progress in Minaturisation and Materials Innovation: Advances in semiconductors, materials science, and nanotechnology require increasingly precise testing and analysis tools, often provided by Judges’ subsidiaries.

Going forward, I expect these trends to continue to benefit the industry, even though at a more modest rate of growth. First, as countries continue to develop and decreasing returns on capital kick in, R&D spending will be a priority to remain competitive. Second, although the major boost towards sustainability probably already occurred, the trend is unlikely to reverse, and additional investments are expected. Finally, education and healthcare are evergreen topics that transcend party politics, and their funding is a key point for every agenda.

The Moat

In this section, I will try to summarise the key sources of Judges’ competitive advantage at the subsidiary and holding level.

The Micro

As already mentioned, most of Judges’ subsidiaries are leaders in niche global markets, and have strong competitive advantages. To better understand why, I will try to answer the following three questions:

What is the need satisfied by the customer?

The majority of Judges’ subsidiaries supply high-precision instruments for cutting-edge R&D and testing projects undertaken globally. These projects often address complex, high-stakes issues, such as climate change, advanced materials, or healthcare innovation, where data accuracy is absolutely critical. As a result, performance is non-negotiable. Sure, price considerations are always relevant and shouldn’t be neglected, but they become of secondary importance when the cost of unreliable instruments could invalidate months, if not years, of research. When institutions invest significant time, coordination, and funding into sensitive research, they simply cannot afford to compromise on instrument quality.

In summary, Judges’ clients require the best-performing instruments to guarantee the validity of results, satisfy regulatory standards, and draw significant conclusions.

Will this need remain in the future?

Yes.

The need for accurate and reliable testing instruments is a cornerstone of innovation and is likely to remain so. If we cannot trust results because of poor instrument quality, what’s the point of even conducting research or testing projects?

Can competitors satisfy the same need?

Now this is the heart of competitive moats: can others do what we are doing and run us out of business?

Well, in this case, I believe the answer is no, and there are a couple of good reasons.

First, the degree of differentiation in Judges’ products is extraordinarily high. The instruments are often tailored to the customer’s needs and are increasingly being protected by patents, making them incredibly costly and difficult to replicate.

Second, even if someone were committed to manufacturing a better instrument, often the game wouldn’t be worth the candle: most of the subsidiaries operate in small, niche markets. The R&D investments required to produce a competing product would be extremely lengthy and expensive, and the potential reward is simply too little for new competitors.

Finally, even if a new competitor were successful in creating a superior instrument, convincing customers to switch supplier would be a difficult task, given the high switching costs characterising most of Judges’ products. Among the others, the sources of these switching costs are:

High degree of customisation and integration: Judges’ products are highly differentiated and are deeply integrated in complex protocols and workflows. Switching providers would mean ensuring that all parts of the workflow still function while also training staff to use the new instruments, resulting in higher delays and costs.

Regulations and standards: In industries like pharmaceuticals and environmental testing, switching instruments can require revalidation of methods and regulatory approvals, adding further time and cost burdens.

Custom software and proprietary data: Judges’ instruments are often accompanied by proprietary software that stores and manages the data collected. Transitioning to a different system would involve significant data migration and compatibility challenges, as well as the risk of data loss.

Searching costs: the strong reputation boasted by Judges’ subsidiaries significantly reduces searching costs for customers. In fact, before switching to a competitor, a customer would need to use time and resources to ensure that the new instrument is legitimate and reliable.

In summary, to compete with Judges’ subsidiaries, companies would have to create instruments significantly more valuable to justify the risk of switching providers, and often, the rewards for manufacturing such a product aren’t worth the risks and costs of developing it.

The Macro

Now, let’s discuss why competing with Judges at a holding level also presents considerable obstacles.

After 20 years of successfully acquiring and developing businesses, Judges now has two considerable advantages over its competitors: size and reputation.

We already mentioned that SDI Group, Judges’ only true competitor at the moment, is about half the size. This means that SDI must be incredibly more careful in making its acquisitions, since, ceteris paribus, a bad acquisition will have a far greater impact on SDI than on Judges. The same is true for new competitors considering adopting a similar model. Scale brings diversification benefits, providing a further margin of safety.

At least as important, Judges managed to build a strong reputation as an acquirer. Owners of small and medium enterprises often care about the exit price as much as the legacy they leave. For many, the company represents the culmination of a lifelong career, and they want to ensure it won’t be completely transformed after their departure. In a conversation with CEO David Cicurel, he explained how prospective sellers would often initially reject Judges’ offer as too low compared to competitors. However, many later returned, having realised that Judges was the best partner thanks to its hands-off, professional approach.

Finally, both scale and reputation allow Judges to progressively secure better financing terms from banks, increasing returns to shareholders while maintaining constant availability of capital for acquisitions.

The Management

Quoting Warren Buffett once again: “When we own portions of outstanding businesses with outstanding managements, our favourite holding period is forever.”.

I think by now it is clear that Judges is an outstanding business, and I will try to persuade you that it also has an outstanding management.

But, before starting, what makes a good manager?

Many books have been written on exceptional CEOs and what traits distinguish them, but the two main aspects that concern me as an investor are capital allocation skills and alignment with shareholders. If a CEO displays these two characteristics, an exceptionally rare thing, I am relatively uninterested in the rest.

The most important figure in Judges is arguably the CEO and founder, David Cicurel. As of today, David still owns roughly 9% of Judges, representing almost all of his wealth. Therefore, the long-term success of Judges is certainly his priority, eliminating the issue with shareholders’ alignment. Furthermore, as the founder of Judges, David has a certain emotional affection for the company, further strengthening his ties with the firm’s performance, reputation, and legacy.

David oversees the entire acquisition process, managing everything from sourcing to closing. His role is to find and acquire profitable businesses that align with Judges’ ecosystem. In other words, David is responsible for allocating Judges’ capital and ensuring it generates strong returns.

To better grasp his capital allocation skills, let’s check the ROE and ROIC levels for Judges in the past 10 years.

As shown, the results are outstanding: both ROIC and ROE levels far exceed any reasonable opportunity cost. Strong ROIC levels, averaging 25%, highlight David’s skill in capital allocation and his understanding of debt as a return amplifier rather than a direct source, something often misunderstood in the private equity industry. For debt to effectively boost returns, a solid base level of profitability (ROIC) must already exist. If those returns are mediocre, the risk of failing to surpass the opportunity cost during downturns increases significantly. Finally, while both ROIC and ROE levels have been trending downwards in the last few years, the drop in 2024 is mainly a result of Geotek’s inability to secure its usual annual coring contract, significantly impacting earnings. ROE and ROIC levels are expected to rebound in 2025 as Geotek has already secured a coring expedition, and operations will resume as normal.

Even though David has an almost immaculate track record, he is human, and as such, he has made a few mistakes on the way. Notably, the acquisitions of Scientifica (£12m) in 2013 and Armfield (£8m) in 2015 turned out to be a flop, generating a negative return on investment. Fortunately, Judges’ diversified structure allows for a few blunders, and David appears to have adopted a more disciplined approach to acquisitions since then. In fact, during a discussion together, he emphasised several times that he’s willing to hold off on deals for years if the right opportunity doesn’t arise, as he did between 2017 and 2019.

Despite these mistakes, the aggregate performance of Judges in the past 20 years has been exceptional, mostly due to David’s capital allocation skills. Ultimately, Judges’ returns depend mainly on acquisitions, and given the extraordinary results achieved, we can safely state that David is a great capital allocator.

A final note on capital allocation: the company has always maintained a policy of paying dividends and increasing them at least by 10% annually. While the dividend impact on owner earnings* (see definition in the appendix) is not massive, it is still significant. Shareholders often argue in favour of dividends, driven by a preference for steady income, the belief that dividends signal financial strength, or the idea that they help discipline management, even when these views may overlook more efficient uses of cash, such as reinvestment or share buybacks. The choice of paying dividends is simply another capital allocation decision, and as such, it has an expected return associated with it. Often, this coincides with the market’s expected return, which in the long run has proven to outperform every other asset class: in most cases, it represents the cost opportunity for most investors. Therefore, a company should pay dividends only when it believes that repurchasing its own shares or reinvesting the proceeds in the operations will generate lower returns than what investors can get from the market. I don’t believe this to be the case for Judges. I would like to see the management sacrifice the dividend to instead aggressively repurchase shares at an attractive price or reinvest the capital in more acquisitions.

Finally, alignment extends across the C-suite, with a significant portion of executives’ personal wealth tied to Judges through equity ownership and stock options. Additionally, the team is also extremely capable and familiar with successful buy-and-builds: both the COO and Group Business Development Director come from Halma, the already mentioned £11 billion group, highlighting Judges’ ability to attract and retain top talent.

The Risks

If anyone tries to convince you that an investment is riskless, chances are you are either being scammed or they simply don’t understand the subject.

In my view, investment risk is not defined by share price volatility or small discrepancies between actual results and estimates. Rather, a risk is an event or trend that significantly changes or obscures my view on the company’s future, resulting in a probable permanent capital loss.

Given this definition, I identified three main risks for Judges Scientific:

Diseconomies of Scale

As Judges increases in size, it will either have to make more acquisitions or acquire bigger targets to maintain its reinvestment and growth rates. There are clear issues with both options: first, the process of finding, understanding, and acquiring businesses is lengthy and complex, and it’s certainly a process you wouldn’t want to rush; second, bigger companies are usually sold at higher multiples, decreasing returns on investment. While I don’t expect Judges to generate the same returns as it did in the past, there is still a risk that increasing scale will push the management outside its comfort zone, leading to costly mistakes.

Despite the above, other successful serial acquirers showed that there is still much room to simultaneously grow and have attractive returns. One above all, Halma now sits at a £11B valuation and generated £2.16B in revenues, more than 15x Judges’ current situation. I believe Judges has a long way to go before having to either adapt its strategy or accept mediocrity, and that the management team has the right profile to take on the challenge.

Key Man Risk

David built this company from the ground, and while he wasn’t alone, arguably most of Judges’ success can be attributed to him. He is now 75 and not planning to retire, and even though there are plenty of examples of seasoned CEOs continuing to do an outstanding work (see Buffett), succession is a topic that deserves to be mentioned.

The most likely profiles to be contenders for David’s role are COO Mark Lavelle (66) and Group Business Development Director Tim Prestidge (54). Both Cambridge graduates, Mark and Tim spent a significant portion of their careers in Halma. Now, they are in charge of Judges’ portfolio companies, contributing to their development and improvement.

While both great profiles, there is a risk that neither will be able to fill David’s shoes.

Reversal of structural trends and increased competition

Finally, there is a risk that the tailwinds supporting Judges’ organic growth could not only lose momentum, but potentially reverse.

In particular, growing concerns over rising national debt are pressuring annual budgets and constraining government spending worldwide. While investments in higher education and R&D projects are a priority, they are not nearly as important as other expenses, including healthcare, primary education, and social security. As a result, were budgets to be reduced, Judges risks incurring important headwinds, especially given its high dependency on university research.

Simultaneously, competition could increase, diluting Judges’ competitive advantage: as SDI Group continues to grow, it too will benefit from diversification and have the opportunity to build a strong reputation with prospective sellers. As a result, competition might increase, and Judges might need to pay more to acquire targets, further shrinking returns.

This being said, everyone’s risk profile is unique: can you go to bed and sleep profoundly with your current holdings?

If the answer is no, the expected returns on your investments are simply not enough to justify your perceived risk.

If the answer is yes, you either don’t know what you are doing or are actually comfortable with the risk-reward profile of your investment. To avoid being in the former category, it is necessary to spend considerable time before making an investment decision, and I have found writing these articles to be an extremely useful discipline tool.

Still, despite the countless hours and efforts we put into something, we remain fallible beings. It is important to acknowledge that there is only as much you can forecast and control, and that often, the biggest risks come from what you don’t and can’t know. That is why, in investing, the concept of margin of safety is so important: it is not to protect you from what you know you don’t know, but from what you don’t even know you don’t know, if that makes sense.

The Valuation

Now that we have a better understanding of the situation and its associated risks, let’s try to determine what price would deliver a sufficient expected risk-adjusted return.

Since I started investing, I have tried several valuation models. While models are useful tools, it’s important to remember that they are meant to support your investment thesis, not to serve as its foundation. Their true value lies in forcing you to reflect on the key assumptions behind your thesis and then testing whether those assumptions make sense numerically.

As a result, I am currently using a very simple model taught to me by my mentor. In practice, it aims at answering only 5 very important questions:

What are the true Owner Earnings?

How much of these will the company reinvest in growth?

At what returns?

For how long?

And, finally, what is my opportunity cost?

For Judges, these are the answers I gave:

First, my estimate of 2025 Owner Earnings per share is roughly £3. To arrive at this figure, I assumed that maintenance CAPEX equals D&A and that the company requires a Net Working Capital equal to 10% of revenues to operate, as stated by the management. Additionally, I added back amortisation of intangibles recognised after acquisitions (net of the tax effect), as I don’t believe it represents a true economic cost. My earnings figure differs from management’s primarily in that I treat a portion of working capital investments as necessary to operate the business, and therefore deduct them from owner earnings. The £3 per share estimate would represent a rebound to 2023 levels, which is in line with the markets’ expectations**.

Second, I believe that Judges will be able to reinvest 80% of its owner earnings in growth. In the past 10 years, the reinvestment rate has been closer to 90%; however, as the firm grows in size, finding enough suitable targets will become more difficult. Judges will either need to significantly increase the number of small acquisitions or start targeting larger companies. The reality will probably be somewhere in the middle, but since the acquisition process is time-consuming and therefore relatively unscalable, I believe the latter option will prevail. Overall, I expect Judges to follow a similar trajectory to Halma, which saw its reinvestment rate decrease in favour of more dividends and buybacks.

Third, I estimate Judges will earn roughly a 17% ROE on its growth reinvestments. To arrive at this figure, I used the same unit economic model I showed at the beginning of the article. However, the average multiple paid on EBIT will increase to 6.5x, driven by the acquisition of larger firms and rising competition.

Fourth, I expect Judges to maintain these reinvestment and return rates for the next 10 years. The pool of potential targets is sufficiently large, especially after Judges expanded its reach to non-UK markets, and the fact that other companies like Halma managed to scale a similar model to over £2B in revenue gives further proof of scalability. Yet, Halma did adapt its model, progressively increasing the acquisition size and expanding into new verticals. I believe Judges will face a similar challenge in about 10 years, when the annual reinvestment need will reach approximately £65M, the same amount paid in cash for Judges’ largest acquisition, Geotek. At that stage, the firm will need to adapt, as sourcing one Geotek-sized acquisition per year may prove too demanding and would likely require a significant strategic rethink.

As a result of the above, owner earnings per share will grow by a compounded ~16.5%, reflecting both inorganic and organic growth. Inorganic growth is computed as the product of the reinvestment rate and marginal ROE. Conversely, I assumed a 3% organic growth rate, a more conservative figure compared to the ~4.2% achieved in the past 10 years. Moreover, I think Judges can maintain a 2% terminal growth rate without engaging in M&A activity. This growth results from ongoing R&D investments, enabling the subsidiaries to sustain their competitive position and at least preserve their value in real terms.

Finally, I used 9% as the discount rate, which is a proxy for my opportunity cost. As already mentioned, I believe my opportunity cost to be the expected return of the market. More specifically, I chose the S&P 500, given its historical overperformance over other indexes and my belief that U.S. companies will maintain their competitive position for at least the next ten years. In other words, aside from rare mispricings in individual stocks, I would expect an S&P 500 ETF to deliver the highest returns over the long run. To obtain the 9% figure, I added the implicit equity risk premium (as computed by Damodaran) to the yield on the 10Y GILT, which represents the risk-free rate in pounds, the currency of the valuation.

A visual representation of the model is shown below:

When I started writing this article (and invested), the share price was roughly £66 per share. At that price, with a 25% discount to fair value, the investment provided enough margin to cover eventual mistakes in the assumptions. While I don’t have a rigorous framework for estimating a margin of safety, I use a mix of rules of thumb and scenario analysis to get comfortable with a valuation. For instance, let’s run a scenario where the risks outlined in the article do materialise: return on equity drops to 13% due to poor capital allocation decisions and diseconomies of scale. Even in this scenario, the fair value would be £65, which would imply I’d still be roughly covering my opportunity cost. Finally, I believe the risk of permanently losing capital in this investment is almost non-existent, given the diversification benefits accrued from scale and the singular moats of Judges’ subsidiaries. For Judges to incur a significant and impactful loss of capital, David would have to make many consecutive, big mistakes, which I find highly improbable.

Nonetheless, as mentioned, risk is subjective, and if one doesn’t feel comfortable with this margin of safety, it’s perfectly fine to wait for a better entry price. However, for strong compounders with little business risk, surprises usually come on the upside, and mistakes of omission tend to be worse than mistakes of commission.

My main takeaway from the valuation is that, at £66 per share, Judges is an investment I expect will exceed my opportunity cost in the long term and will provide an adequate risk-adjusted return.

While most likely the numbers of my forecast will be wrong, I very much agree with John M. Keynes’ observation: “It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong”.

Conclusion

In summary, Judges Scientific is one of the few great serial acquirers operating today. The competitive dynamics of the business, coupled with outstanding management, make this a strong candidate for every long-term investor. While today’s price (£81 per share) might not provide enough cushion to invest, I hope that this article painted a clear picture of what I believe is a great business, one that every value investor should have on the watchlist.

If you made it this far, thanks for your patience (I’m honestly impressed).

I hope the return on the time you invested reading this is well above your opportunity cost, and I wish you a pleasent summer ahead.

Appendix

*Owner Earnings

Quoting Berkshire’s 1986 letter to shareholders, “Owner Earnings represent (a) reported earnings plus (b) depreciation, depletion, amortization, and certain other non-cash charges such as Company N's items (1) and (4) less (c) the average annual amount of capitalized expenditures for plant and equipment, etc. that the business requires to fully maintain its long-term competitive position and its unit volume. (If the business requires additional working capital to maintain its competitive position and unit volume, the increment also should be included in (c) . However, businesses following the LIFO inventory method usually do not require additional working capital if unit volume does not change.)”.

In other words, owner earnings represent the capital available to the owners, net of the investments necessary to maintain the company’s current competitive position. These earnings are the true focus of capital allocation: they can either be distributed to shareholders through dividends or buybacks, or reinvested for growth.

For a more thorough explanation of owner earnings, I will leave Berkshire’s 1986 letter here.

**Market expectations

While equity reports and analyst estimates have been proven to be significantly wrong on the long run projection of earnings, their estimates for next year's earnings are quite accurate and provide a useful benchmark to check one’s short-term assumption.